In the past, UK’s new Prime Minister Keir Starmer was among those expressing concern for free speech on the internet and how a law that results in fines and arrests because of social media posts could have “a chilling effect on free speech.”

Right now, his government is carrying out mass arrests of people who get convicted for precisely that reason: the things they’ve said on the internet.

But back in 2012, speaking about the Communications Act 2003 and its section 127, Starmer was worried about the law resulting in “a lot of prosecutions” – even though his comments overall can hardly be interpreted as coming from a strong advocate for freedom of expression.

Referring to what is considered “grossly offensive messages” and criminalization of communications of that nature, Starmer wanted to see what he called a high threshold for people’s right to be offensive and insulting.

That, he said, needed to be protected. Otherwise, a large number of prosecutions would have “a chilling effect on free speech, and I think that’s a very important consideration,” Starmer told the BBC.

According to him, the criminal offense here was “overarching,” hence the fear that it would apply to the type of communications he mentioned, and if the only response was a criminal one, he warned, “there might be the temptation to resort too quickly to that response.”

In 2012, Starmer would have preferred to have the option of using different kinds of remedies, such as lodging a complaint.

The “high threshold,” as he advocated for it, was to prosecute what would be considered online harassment campaigns that presented “a credible and genuine threat” and differentiate that from speech that is simply grossly offensive.

But Starmer wasn’t above prosecuting those expressing themselves in that way, either – he wanted “a slightly different” approach and a set of guidelines that would be used to determine when grossly offensive speech was enough to prosecute people over.

When pressed about specific scenarios where people were making “unpleasant” comments about British soldiers who were killed or missing children – and were at the time prosecuted for that, having to pay fines or were ordered community service, Starmer said:

“Well we live in a democracy and if free speech is to be protected there has to be a high threshold people have the right to be offensive, they have the right to be insulting and that has to be protected.”

Effectively, Starmer wasn’t challenging the law as such but was in favor of avoiding a large number of prosecutions. And he supported to all intents and purposes pressuring social media companies into removing content, citing their “responsibility.”

“In many of these cases the appropriate response may be for you (social media companies) to take this material down swiftly and that may reduce the requirements for a criminal prosecution,” he said.

The debate is not abating over the way protests and riots in the UK have been handled from the viewpoint of the crackdown on free speech online, an approach to the crisis chosen by Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s government.

Among his critics is Baroness Claire Fox, who is worried that the government is essentially intimidating people when it warns them to “think before they post,” and that this produces an atmosphere in society akin to that once present in old-style communist regimes.

“A Stasi-like (former East Germany secret police) atmosphere of looking over your shoulder in case somebody’s listening,” as Fox put it.

She is concerned that things won’t be looking up going forward, either, and believes Starmer’s government will be responsible for introducing even more “explicit censorship” by way of expanding the Online Safety Act – an already controversial, sweeping censorship law – to cover “legal but harmful content.”

The baroness also noted that currently, the authorities are moving in the direction of using legal means to go after people not only for speech that is found to have incited violence or rioting – but also for speech that they decide could have had that effect.

Fox spoke about the lack of clarity over what hate speech, misinformation or disinformation are, noting that these are “very often subjectively interpreted.”

As for “two-tier policing” – that is, people receiving different treatment that is believed to be the result of a politicization of law enforcement – Fox doesn’t think some people perceive that to be true “because somebody saw a meme on X.”

“It’s because that idea of two-tier policing spoke very deeply to the fact that people do not feel they get fairly treated by the police,” she said.

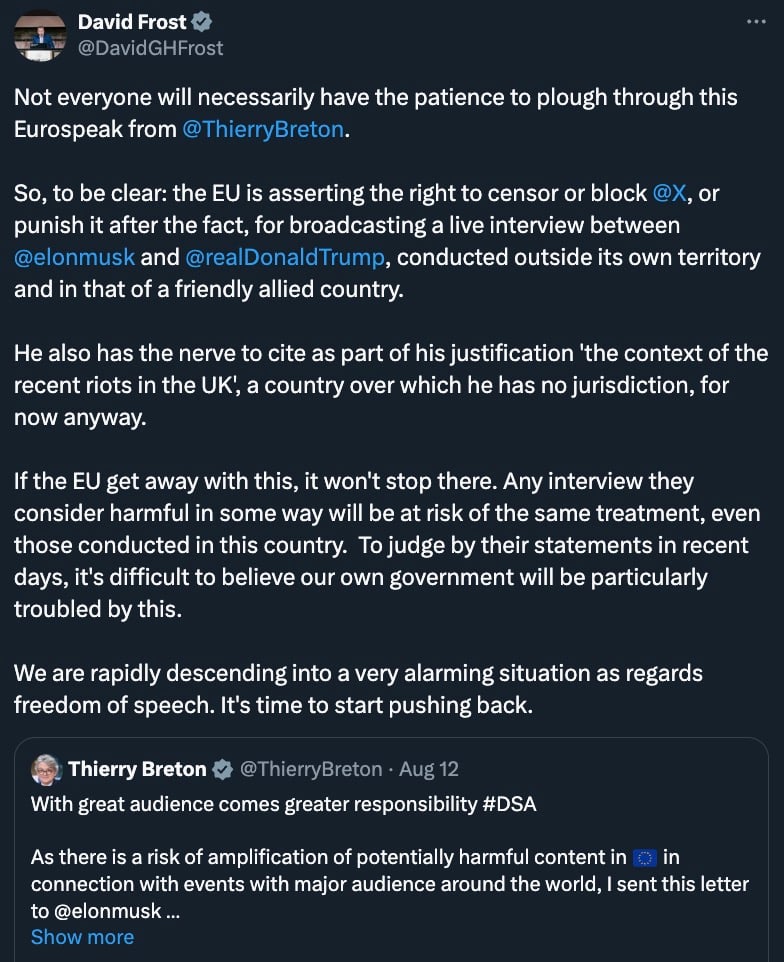

And while all this is happening in the UK, some politicians there, like Lord David Frost, are keeping an eye on the EU – specifically the extraordinary case of Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Breton threatening X with censorship ahead of Elon Musk’s Donald Trump interview.

Frost slams this as the EU saying it could “censor or block X, or punish it after the fact, for broadcasting a live interview conducted outside its own territory, and in that of a friendly allied country.”

Frost is also not pleased that Breton went for the UK riots as a way to justify this move.

But even if the EU doesn’t have jurisdiction over the UK, as Frost, a member of the House of Lords, remarked, the government’s actions in his country are clearly emboldening others to try to crack down on online speech.

“If the EU get away with this, it won’t stop there,” Frost warned, adding, “Any interview they consider harmful in some way will be at risk of the same treatment, even those conducted in this country.”

And he summed up the situation: “To judge by their statements in recent days, it’s difficult to believe our own government will be particularly troubled by this.”

Total Vindication: NATO Admits Russia Did Not Blow Up Nordstream Pipeline